And, it is finally done.

Biker God

Saturday, 1 March 2014

Thursday, 5 December 2013

"Find the crow" pages.

Here are the first 4 pages without the shading.

Pencil work will be quite essential for me considering I am not inking my work, so, a strong drawing and clean pencil is what I need the most for this project. Even though it takes time to do it properly.

See you soon with the next 4 pages. The sooner the better.

p.s. the perspectives were a pain in the genitals.

*edit

With all the pain and suffering I managed to upload another page.

BAM!

Now, back to the (torture) desk for next pages...

*edit

Hello again!

Here are 2 other new pages.

One more to go.

*later(much later) edit

IT IS DONE! For now.

Now for the rendering process...

*edit

With all the pain and suffering I managed to upload another page.

BAM!

Now, back to the (torture) desk for next pages...

*edit

Hello again!

Here are 2 other new pages.

One more to go.

*later(much later) edit

IT IS DONE! For now.

Now for the rendering process...

Wednesday, 4 December 2013

Script

Here's the script t hat I wrote for this Biker God episode.

Page

one

Panel

1.

Up worms eye shot of a desert sand dune. On

top of a dune lies something that resembles a marker.

Panel

2.

Same view of the dune, close shot of a foot

being dug deep into the sand.

Panel

3.

Same view of the same dune, full shot of Em

close to the top of the dune, trying to crawl over it.

Panel

4.

Down birds eyeview shot of Em being on top

of the dune, next to the marker. He is looking at the vastness of the desert

lying ahead of him. I intend to have the perspective as stretched as possible.

Caption

“I was lost…”

Panel

5.

Medium long shot of Em looking tired. He is

facing the reader, having his head and shoulders tilted, his chin slightly

upwards so that light reflects from his glasses.

Panel

6.

Medium long shot of Em’s body. His knees

are bended and he seems to be collapsing.

Panel

7.

Full (worms eye

view) shot of Em on his knees. The top of the dune is seen arched to the left,

gradually disappearing in the far distance, where a strange heat distorted

figure can be seen walking towards him.

Page two.

Panel 1.

Extreme close

shot of the buffalo’s foot stirring up the sand.

Buffalo: “Find…”

Panel 2.

Extreme close up

to Em’s eyes. His head is tilted to the left, the direction of the buffalo’s

voice.

Buffalo: “The…”

Panel 3.

Caption: “And scared…”

Full (worms eye

view) shot. Em is on his knees, he realizes that next to him there’s a buffalo

skeleton talking to him. He has his arm raised and he leans to the opposite

position of where the buffalo is, as he would lean if he were trying to escape.

Buffalo: “Crow…”

Panel 4.

Medium close shot

of Em falling down due to his fright. He is involuntarily trying to cushion his

fall with his elbow.

Panel 5.

Far shot of Em

tumbling downhill. (The direction of Em’s fall will be right. Considering the

way I picture the storyboard, I want these first pages to produce an uneasy

feeling by shifting some of the actions in the panels as opposed to the normal

way of reading a page[left to right])[it’s

better explained on paper]

(This is also

necessary to point out that Em’s tendency to back down, to remain in his

comfort zone, which ends with this actual fall as it will later be seen.)

Panel 6.

Caption: “I have almost given up”

Medium shot of Em

lying silent, his arms and legs are twisted in a strange position (his right

arm going under his body to the left side where it lies in a vertical position

his right leg flexed backwards touching his posterior while his other leg is

flexed from the knee touching his left side of the thorax), face first in the

sand, after his tumultuous tumble down the dune.

Panel 7.

Em lies in a

similar position (his right arm and leg are in normal positions)

Em: “ouch”

Page three.

Panel 1.

An up (worm eye)

shot of Em getting up. He is presented in 3 positions. A medium close shot

while trying to push himself up, a medium long shot of his legs as he’s trying

to walk away (his hand position over his bended right leg hints to the hit he

received on his fall) and a far shot with him on the right of the panel looking

to the left at the sun.

Panel 2.

Down shot of Em

walking up a dune. He is presented in 4 positions. In the first one on the far

left upper corner of the panel he happily spots a huge bottle, around which the

dune swirls. On the second position he is inspecting the bottle. The third

position is a full shot of him walking up the dune, deflated by his failure to

find water. On the last pose he is in a medium long shot, struggling to climb

up the dune.

Panel 3.

Caption: “And when I did, it came to me again”

A full up shot

worm eye view of Em looking at the sky. Around him the desert unwraps its

vastness. Bottles can be seen on and around the strange dunes.

Page four.

Panel 1.

Buffalo: “Find…”

Em: “No.”

Medium close shot

of Em on his knees

Panel 2.

Buffalo: “the…”

Em: “I can’t.”

Full shot of Em

on his knees and hands, with his head down, looking tired and depressed.

Panel 3.

Buffalo: “crow…”

Close up shot.

Em’s had can be seen facing downwards, on the bottom left of the panel, the

buffalo’s boney snout can be seen on the upper right of the panel.

Panel 4.

Em: “I don’t

trust myself to do it.”

Buffalo: “trust…

don’t trust?”

Em and the

buffalo are standing face to face.

Panel 5.

Extreme close up

to Em’s face. Em looks like he just woke up. (Em’s reaction portrays a subtle

realization of his error in his way of perceiving situations that are out of

his comfort zone.)

Panel 6.

Extreme close up

to Em’s hand reaching for the buffalo’s jaw.

Panel 7.

Extreme close up

on Em’s hand being pulled by the buffalo.

Panel 8.

Medium close up

of Em clenching his fist.

Page 5.

Panel 1.

Birds eye view of

Em walking up a dune. He appears in 3 positions. An extreme far shot, a far

shot and a full shot.

Panel 2.

Long 3 shot of a

dune half covering a huge bottle. Em is presented in 3 positions. The first one

is getting down the steep angle of the dune. The second one is stumbling down,

near the bottom of the dune. The third one is resting, leaning on the bottle,

huffing and puffing. The sand near the bottle is littered with bones, and Em

doesn’t notice them.

Panel 3.

Buffalo: “Find…”

Em: “I know”

Buffalo: “The…”

Em: “I know, I’m just…”

Full single shot

of Em holding one hand on the glass of the bottle and one hand of his knee, facing

downwards and trying to catch his breath. In the background the buffalo is

facing him.

Panel 4.

Buffalo: “Cr…”

Close shot of the

buffalo.

Panel 5.

Close shot of the

buffalo turning to the right as he would have noticed something.

Panel 6.

Em: “…resting?”

Em faces upwards

and sees that the buffalo is missing.

Page 6

Panel 1.

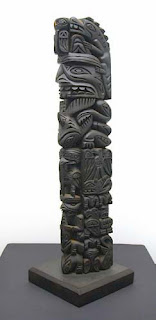

Worm’s eye view

of the totem and the bottle that Em’s resting in the background. The totem is

holding a huge bottle that springs water. At the base of the totem, is a medium

size pond. In the background we can see Em looking amazed while facing the

buffalo’s direction. In the far background the dunes are gradually disappearing

in a misty like manner.

Panel 2.

Medium shot of Em

smiling at the realization that they found water.

Panel 3.

Close up to the

buffalo’s skull. The buffalo is drinking water. Being all bones, the water sort

of behaves like it would in 0 G. (When the buffalo sticks its snout inside the

water and the paint on his snout gets washed, leaving him without the

protection of a tattoo.)

Page 7

Panel 1.

Medium shot of

the buffalo facing Em. His head is tilted on a side; water is dripping from his

mouth. His tattoos are gone.

Buffalo: “…run”

Panel 2.

Worm’s eye view

of the buffalo being ripped apart by hands emerging from the sand.

Panel 3.

Worm’s eye view

from Em’s back, of Em falling backwards, being attacked by some of the hands

that emerged from the sand. In the background a couple of hands are

distinctively holding the buffalo’s skull.

Bones fly around,

and one of the bones pierces Em’s t-shirt, this being another reason for his

fall backwards (he tries to dodge the “bullets”)

Panel 4.

Em: “no!”

Horizontally

extremely close shot of Em, being on the ground, with hands creeping towards

him

Panel 5.

Buffalo: “run!”

Same type of shot,

this time of the buffalo’s skull being held by a couple of hands, with more

hands creeping in.

Panel 6.

Em: “no”

Same type of

shot, this time of Em is violently being grabbed and pulled by the hands that

increased in number

Panel 7.

Same type of

shot, the buffalo’s head is being ripped in half.

Buffalo: “run!”

Em: ”no!”

(I planned this

page to have a bit of a subtext. First of all the buffalo is being attacked due

to his lack of ink, his lack of tattoos. This is what happens to Em as well,

but it firstly happens to the buffalo due to his proximity to the totem. The

Mojave Indians used to believe that if you were dead and you had no tattoos at

the time of your death, after your death your spirit would be dragged into rat

holes where it would be stuck for eternity. I took this motif and gave it a bit

of a twist, considering that the whole biker god universe is some kind of

spirit world, somewhere beyond life or death with all sorts of strange things

free to happen. Second of all, I intended the “run” “no” dialogue that the

buffalo and Em have, to be a wee bit…I wouldn’t say misleading, maybe tangled

is the better word. You can interpret Em’s “no” shouts as being shouted for

more than one reason. First of all, he could be shouting “no” as a reaction to

the violent situation he is in. He is shocked and frightened, he denies the

idea that he is in a situation from which he has quite slim chances to get out

alive from. The second reason would be his empathy. He refuses to acknowledge

the certain end of the single “living” thing that helped him on his journey,

and his inability to help him in the smallest way possible. The third reason is

similar to the second one on a certain level but different. Em denies running

away, due to the realization of his frivolous will. This happened when he was

confronted with the most casual play of words that the buffalo repeated

[trust…don’t trust], in the episode that Em had admitted to have given up. In

other words, he came to the realization that if he cannot trust himself, he

cannot trust his mistrust in himself as well, and now he was confronted with a

situation that required him to trust himself. I plan on keeping the angles of page7

and the last panels on page 7 as close to horizontal, thus depicting the idea

of Em’s stillness(both mental[he is shocked, frightened, unable to comprehend

the situation] and physical[being bound to the ground and unable to move]),

besides making the threat more…menacing)

Page 8

Panel 1.

A series of close

shots and extreme reactions of Em, or a long shot of Em in different poses. Em

will grab the bone that pierced his t-shirt, and use it to fight some of the

hands. He shouts and cries and in the end a hand drops “dead” next to the buffalo’s

skull.

(I want to leave

myself the creativity to figure this out on paper. I think that it would most

likely be better resolved under the influence of spontaneity. I will probably

use a series of small panels and rush the viewer through the actions and Em’s

emotional reactions and end it with the hand close to the skull[mislead the

reader for a moment that, that hand could be Em’s]).

Panel 2.

Crow: “no...”

Extreme close up

to the skull mask that the Crow is wearing.

Panel 3.

Crow: “I

somehow don’t trust myself to believe you!”

Medium 2 shot of

the Crow stretching his bow, Em is facing us with his back, his holding his

hands up.

Panel 4.

Crow: “After all that, you had the strength to find

me? How? ”

Em: “Well…”

Medium shot of Em

holding his hands up, looking beaten up and tired. He has a faint smile,

something that is close to crying.

Panel 5.

Em: “I figured that, if you can’t trust yourself, can

you trust not trusting yourself?”

Close up to Em’s

face. He is crying and smiling at the same time. A true sincere smile and tears

in his eyes.

(There is more

than one reason that I’ve chosen to depict Em crying at the end. First of all,

he is recovering after a shock. It is normal for a human being to go through

these kinds of conflicting emotional states after serious stress or shock. The

second reason is his realization of his goal, he found the Crow, his journey

ends for the moment, and he is safe. The third reason is his empathic nature. He

mourns the death of the buffalo and realizes the help [from more than one point

of view] that the buffalo has given him. He is crying as a result of his

realization of his act of maturing, of growing up, of being aware of the

change, a process that is both hurtful and joyful.)

The End

Tuesday, 3 December 2013

Research

Need to say this from the start.

Unfortunately I was wise enough to manage to erase the scans I had with the research sketchbook, that also had spontaneous sketches in it...but it's ok, I still have all the info with the things that got into that sketchbook.

A totem is a being, object, or symbol representing an animal or plant that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, group, lineage, or tribe, reminding them of their ancestry (or mythic past).

In kinship and descent, if the apical ancestor of a clan is nonhuman, it is called a totem.

Normally this belief is accompanied by a totemic myth. They have been around for many years.

They are usually in the shape of an animal, and every animal has a certain personality, e.g Owl:

The Owl - Wisdom, silent and swift and wise.

Although the term is of Ojibwe origin in North America, totemistic beliefs are not limited to Native Americans and Aboriginal peoples in Canada.

Similar totem-like beliefs have been historically present in societies throughout much of the world, including Africa, Arabia, Asia, Australia, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and the Arctic polar region.

In modern times, some single individuals, not otherwise involved in the practice of a tribal religion, have chosen to adopt a personal spirit animal helper, which has special meaning to them, and may refer to this as a totem.

This non-traditional usage of the term is prevalent in the New Age movement and the mythopoetic men's movement.

There are taboos against killing clan animals, as humans are kin to the animals whose totems they represent. In some cases, totem spirits are clan protectors and the center of religious activity.

Even infants were provided with

protective charms. Examples of these are the "spiderwebs" hung on the

hoop of a cradle board. These articles consisted of wooden hoops about

3½ inches in diameter filled with an imitation of a spider's web made of

fine yarn, usually dyed red. In old times this netting was made of nettle

fiber. Two spider webs were usually hung on the hoop, and it was said that they

"caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider's web catches and

holds whatever comes in contact with it."

Even infants were provided with

protective charms. Examples of these are the "spiderwebs" hung on the

hoop of a cradle board. These articles consisted of wooden hoops about

3½ inches in diameter filled with an imitation of a spider's web made of

fine yarn, usually dyed red. In old times this netting was made of nettle

fiber. Two spider webs were usually hung on the hoop, and it was said that they

"caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider's web catches and

holds whatever comes in contact with it."

Native

American and First Nations cultures have diverse religious

beliefs. There was never one universal Native American religion or spiritual

system.

Native

American and First Nations cultures have diverse religious

beliefs. There was never one universal Native American religion or spiritual

system.

Though many Native American cultures have traditional healers, ritualists, singers, mystics, lore-keepers and "Medicine People", none of them ever used, or use, the term "shaman" to describe these religious leaders.

Rather, like other indigenous cultures the world over, their spiritual functionaries are described by words in their own languages, and in many cases are not taught to outsiders.

Not all Indigenous communities have

roles for specific individuals who mediate with the spirit world on behalf of

the community. Among those that do have this sort of religious structure,

spiritual methods and beliefs may have some commonalities, though many of these

commonalities are due to some nations being closely related, from the same

region, or through post-Colonial governmental policies leading to the combining

of formerly independent nations on reservations. This can sometimes lead to the

impression that there is more unity among belief systems than there was in antiquity.

Not all Indigenous communities have

roles for specific individuals who mediate with the spirit world on behalf of

the community. Among those that do have this sort of religious structure,

spiritual methods and beliefs may have some commonalities, though many of these

commonalities are due to some nations being closely related, from the same

region, or through post-Colonial governmental policies leading to the combining

of formerly independent nations on reservations. This can sometimes lead to the

impression that there is more unity among belief systems than there was in antiquity.

This form of ceremony was brutally suppressed by the

United States military with the death of 128 Sioux at the massacre of Wounded Knee.

This form of ceremony was brutally suppressed by the

United States military with the death of 128 Sioux at the massacre of Wounded Knee.

The primary function of these "medicine elders"

is to secure the help of the spirit world, including the Great

Spirit (Wakan Tanka in the language of the Lakota

Sioux), for the

benefit of the entire community.

Sometimes the help sought may be for the sake of healing disease, sometimes it may be for the sake of healing the psyche, sometimes the goal is to promote harmony between human groups or between humans & nature. So the term "medicine man/woman" is not entirely inappropriate, but it greatly oversimplifies and also skews the depiction of the people whose role in society complements that of the chief. These people are not the Native American equivalent of the Chinese "barefoot doctors", herbalists, nor of the emergency medical technicians who ride rescue vehicles.

To be recognized as the one who performs this function of bridging between the natural world and the spiritual world for the benefit of the community, an individual must be validated in his role by that community. Medicine men and women study through a medicine society or from a single teacher.

Native Americans tend to be quite reluctant to discuss issues about medicine or medicine people with non-Indians.

In some cultures, the people will not even discuss these matters with Indians from other tribes. In most tribes medicine elders are not expected to advertise or introduce themselves as such. As Nuttall writes, "An inquiry to a Native person about religious beliefs or ceremonies is often viewed with suspicion.

One example of this was the Apache medicine cord or Izze-kloth, whose purpose and use by Apache medicine elders was a mystery to nineteenth century ethnologists because "the Apache look upon these cords as so sacred that strangers are not allowed to see them, much less handle them or talk about them."

The 1954 version of Webster's New World Dictionary of

the American Language, reflects the poorly grounded perceptions of the

people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that

time: "a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and

controlling spirits." In effect, such definitions were not explanations of

what these "medicine people" were to their own communities, but

instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote

observers when they tried to categorize these individuals.

The 1954 version of Webster's New World Dictionary of

the American Language, reflects the poorly grounded perceptions of the

people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that

time: "a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and

controlling spirits." In effect, such definitions were not explanations of

what these "medicine people" were to their own communities, but

instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote

observers when they tried to categorize these individuals.

The term "medicine man/woman" like the term "shaman", has been criticized by Native Americans, as well as other specialists in the fields of religion and anthropology.

The term "medicine man/woman" was also frequently used by Europeans to refer to African traditional healers, also known as "witch doctors" or "fetish men/women".

Ritual masks occur throughout the world, and although they

tend to share many characteristics, highly distinctive forms have developed.

Ritual masks occur throughout the world, and although they

tend to share many characteristics, highly distinctive forms have developed.

The function of the masks may be magical or religious; they may appear in rites of passage or as a make-up for a form of theatre.

Equally masks may disguise a penitent or preside over important ceremonies; they may help mediate with spirits, or offer a protective role to the society who utilise their powers.

Biologist Jeremy Griffith has suggested that ritual masks, as representations of the human face, are extremely revealing of the two fundamental aspects of the human psychological condition: firstly, the repression of a cooperative, instinctive self or soul; and secondly, the extremely angry state of the unjustly condemned conscious thinking egocentric intellect.

Pueblo craftsmen produced impressive work

for masked religious ritual, especially the Hopi and Zuni.

Pueblo craftsmen produced impressive work

for masked religious ritual, especially the Hopi and Zuni.

The kachinas, god/spirits, frequently take the form of highly distinctive and elaborate masks that are used in ritual dances.

These are usually made of leather with appendages of fur, feathers or leaves.

Some cover the face, some the whole head and are often highly abstracted forms.

Navajo masks appear to be inspired by the Pueblo prototypes.

Since prehistoric times, Native

American sculptures have been very popular.

Since prehistoric times, Native

American sculptures have been very popular.

Archeologists have found many carvings such as fetishes. Fetishes are the Native American sculptures or carvings of animals that are often used in religious ceremonies.

Some Native American sculptures will

have a coral heart line on both sides. This heart line usually runs from

the mouth or nose to where the heart lies.

Some Native American sculptures will

have a coral heart line on both sides. This heart line usually runs from

the mouth or nose to where the heart lies.

An arrowhead may symbolize the heart line or life force.

Some fetishes may also come with decorations such as turquoise, coral, an arrowhead, or feathers. These are considered offerings to evoke the spirit of the fetish.

Unfortunately I was wise enough to manage to erase the scans I had with the research sketchbook, that also had spontaneous sketches in it...but it's ok, I still have all the info with the things that got into that sketchbook.

TOTEMS

A totem is a being, object, or symbol representing an animal or plant that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, group, lineage, or tribe, reminding them of their ancestry (or mythic past).

In kinship and descent, if the apical ancestor of a clan is nonhuman, it is called a totem.

Normally this belief is accompanied by a totemic myth. They have been around for many years.

They are usually in the shape of an animal, and every animal has a certain personality, e.g Owl:

The Owl - Wisdom, silent and swift and wise.

Although the term is of Ojibwe origin in North America, totemistic beliefs are not limited to Native Americans and Aboriginal peoples in Canada.

Similar totem-like beliefs have been historically present in societies throughout much of the world, including Africa, Arabia, Asia, Australia, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and the Arctic polar region.

In modern times, some single individuals, not otherwise involved in the practice of a tribal religion, have chosen to adopt a personal spirit animal helper, which has special meaning to them, and may refer to this as a totem.

This non-traditional usage of the term is prevalent in the New Age movement and the mythopoetic men's movement.

Native

North American totems:

Native

North American totems:

The word totem comes from the

Ojibway word dodaem and means "brother/sister kin".

It is the

archetypal symbol, animal or plant of hereditary clan affiliations.

People from the same clan have the same clan totem and are considered immediate family.

It is taboo to marry someone of the same clan.

People from the same clan have the same clan totem and are considered immediate family.

It is taboo to marry someone of the same clan.

The Ojibway scholar Basil H.

Johnston defines dodaem, or totem, as "that from which I draw my purpose,

meaning, and being," and states that "the bonds that united the

Ojibway-speaking people were the totems."

He further asserts that the

feeling of oneness among people that occupy a vast territory is based not on

political, economic, or religious considerations but on totemic symbols that

"made those born under the signs one in function, birth, and

purpose."

This means that men and women belonging to the same totem regarded

one another as brothers and sisters having kinship obligations to each other.

In North America, there is a certain

feeling of affinity between a kin group or clan and its totem. There are taboos against killing clan animals, as humans are kin to the animals whose totems they represent. In some cases, totem spirits are clan protectors and the center of religious activity.

North American totem poles:

Totem poles of the Pacific Northwest of North America are monumental poles of heraldry;

the word totem is derived from the Ojibwe

word odoodem [oˈtuːtɛm], meaning "his kinship group".

They feature many different designs

(bears, birds, frogs, people, and various supernatural beings and aquatic

creatures) that function as crests of families or chiefs.

They recount stories

owned by those families or chiefs, and/or commemorate special occasions.

DREAMCATCHERS

In some Native American cultures, a dreamcatcher (or dream catcher; Lakota: iháŋbla gmunka,

Ojibwe: asabikeshiinh,

the inanimate form of the word for "spider" or Ojibwe: bawaajige

nagwaagan meaning "dream snare") is a handmade object based on a willow

hoop, on which is woven a loose net or web.

The dreamcatcher is then decorated with sacred items such

as feathers and beads.

Origin:

Origin:

Dreamcatchers originated with the Ojibwe people and were later adopted by some

neighboring nations through intermarriage and trade. It wasn't until the Pan-Indian Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, that they

were adopted by Native Americans of a number of different nations. Some consider the

dreamcatcher a symbol of unity among the various Indian Nations, and a general

symbol of identification with Native American or First Nations cultures. However, many other Native Americans have come to

see dreamcatchers as over-commercialized, offensively misappropriated and misused by non-Natives.

The Ojibwe people have an ancient legend as to the origin

of the dreamcatcher. Storytellers used to speak of the Spider Woman, known as

Asibikaashi, she took care of the children and the people on the land.

Eventually, the Ojibwe Nation spread to the corners of North America it was

difficult for Asibikaashi to reach all the children.

So, the mothers and

grandmothers would weaved magical webs for the children, using willow hoops and

sinew or cordage made from plants. The dreamcatchers would filter out all bad

dreams and only allow good thoughts to enter our mind. Once the sun rises, all

bad dreams just disappear.

American ethnographer Frances Densmore writes in her book Chippewa Customs:

Even infants were provided with

protective charms. Examples of these are the "spiderwebs" hung on the

hoop of a cradle board. These articles consisted of wooden hoops about

3½ inches in diameter filled with an imitation of a spider's web made of

fine yarn, usually dyed red. In old times this netting was made of nettle

fiber. Two spider webs were usually hung on the hoop, and it was said that they

"caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider's web catches and

holds whatever comes in contact with it."

Even infants were provided with

protective charms. Examples of these are the "spiderwebs" hung on the

hoop of a cradle board. These articles consisted of wooden hoops about

3½ inches in diameter filled with an imitation of a spider's web made of

fine yarn, usually dyed red. In old times this netting was made of nettle

fiber. Two spider webs were usually hung on the hoop, and it was said that they

"caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider's web catches and

holds whatever comes in contact with it."

Traditionally, the Ojibwe construct

dreamcatchers by tying sinew strands in a web around a small round or

tear-shaped frame of willow (in a way roughly similar to their method for

making snowshoe webbing). The resulting

"dream-catcher", hung above the bed, is used as a charm to protect

sleeping people, usually children, from nightmares.

The Ojibwe believe that a

dreamcatcher changes a person's dreams. According to Konrad J. Kaweczynski,

"Only good dreams would be allowed to filter through… Bad dreams would

stay in the net, disappearing with the light of day." Good dreams would pass through and slide down the feathers

to the sleeper.

Another explanation of Lakota

origin, "Nightmares pass through the holes and out of the window. The good

dreams are trapped in the web, and then slide down the feathers to the sleeping

person."

Dreamcatcher

Parts:

Dreamcatcher

Parts:

When dreamcatchers were originally

made, the Ojibwe people used willow hoops and sinew or cordage made from

plants.

The shape of the dreamcatcher is a circle because it represents how

giizis- the sun, moon, month- travel each day across the sky.

There is meaning to every part of the dreamcatcher from the

hoop to the beads embedded in the webbing. The strings, or sinews are tied at several points on the

circle, with the number of points on the dreamcatcher having different

meanings:

-13 points- the 13 phases of the moon

-8 points-the number of legs on

the spider woman of the dreamcatcher legend

-7 points- the seven prophecies of

the grandfathers

-6 points- an eagle or courage

-5 points-the star.

The feathers placed at the bottom of the dreamcatcher also

had meaning. It meant breath, or air, it is essential for life. If an owl

feather was used, it means wisdom, which was a woman's feather. IF an eagle's

feather was used it is meant for courage, and was a man's feather.

SHAMANISM AND MEDICINE MEN/WOMEN

Native

American and First Nations cultures have diverse religious

beliefs. There was never one universal Native American religion or spiritual

system.

Native

American and First Nations cultures have diverse religious

beliefs. There was never one universal Native American religion or spiritual

system. Though many Native American cultures have traditional healers, ritualists, singers, mystics, lore-keepers and "Medicine People", none of them ever used, or use, the term "shaman" to describe these religious leaders.

Rather, like other indigenous cultures the world over, their spiritual functionaries are described by words in their own languages, and in many cases are not taught to outsiders.

Many of these indigenous religions

have been grossly misrepresented by outside observers and anthropologists, even

to the extent of superficial or seriously mistaken anthropological accounts

being taken as more authentic than the accounts of actual members of the

cultures and religions in question. Often these accounts suffer from "Noble Savage"-type romanticism and racism.

Some contribute to the fallacy that Native American cultures and religions are

something that only existed in the past, and which can be mined for data

despite the opinions of Native communities.

Not all Indigenous communities have

roles for specific individuals who mediate with the spirit world on behalf of

the community. Among those that do have this sort of religious structure,

spiritual methods and beliefs may have some commonalities, though many of these

commonalities are due to some nations being closely related, from the same

region, or through post-Colonial governmental policies leading to the combining

of formerly independent nations on reservations. This can sometimes lead to the

impression that there is more unity among belief systems than there was in antiquity.

Not all Indigenous communities have

roles for specific individuals who mediate with the spirit world on behalf of

the community. Among those that do have this sort of religious structure,

spiritual methods and beliefs may have some commonalities, though many of these

commonalities are due to some nations being closely related, from the same

region, or through post-Colonial governmental policies leading to the combining

of formerly independent nations on reservations. This can sometimes lead to the

impression that there is more unity among belief systems than there was in antiquity.

Navajo

medicine men and women, known as "Hatałii", use several methods to diagnose the

patient's ailments. The Hatałii will select a specific healing song for

that type of ailment. Navajo healers must be able to correctly perform a

traditional healing ceremony from beginning to end. If they do not, the

ceremony will not work. Training a Hatałii to perform ceremonies is extensive,

arduous, and takes many years. The apprentice learns everything by watching his

teacher, and memorizes the words to all the songs. Many times, a medicine man

or woman cannot learn all sixty of the traditional ceremonies, so will opt to

specialize in a select few.

Extirpation

in North America:

Extirpation

in North America:

With the arrival of European settlers

and colonial administration, the practice of

Native American traditional beliefs was discouraged and Christianity was

imposed upon the indigenous people. In most communities, the traditions were

not completely eradicated, but rather went underground, and were practiced

secretly until the prohibitive laws were repealed.

About 1888, a mass movement known as

the Ghost Dance started among the Paviotso (a branch

of the Pah-Utes in Nevada) and swept through many tribes of Native

Americans.

The

belief was that through practicing the Ghost Dance, a messiah

would come with rituals that would make the white man disappear and bring back

game and dead native Americans.

This spread to the Plains tribes, who were starving due to

the depletion of the buffalo. Some Sioux, the Arapahos, Cheyennes and Kiowas

accepted the doctrine.

This form of ceremony was brutally suppressed by the

United States military with the death of 128 Sioux at the massacre of Wounded Knee.

This form of ceremony was brutally suppressed by the

United States military with the death of 128 Sioux at the massacre of Wounded Knee.

During the last hundred years,

thousands of Native American and First Nations children from many different communities were sent into Indian boarding schools in an effort to destroy tribal

languages, cultures and beliefs.

"Medicine man" or "medicine woman"

are English terms used to describe traditional healers and spiritual leaders among Native American and other

indigenous or aboriginal peoples. Anthropologists tend to prefer the term

"shaman,"

a specific term for a spiritual mediator from the Tungusic

peoples of Siberia.The medicine man and woman in North America

Role in native society:

Role in native society:

The primary function of these "medicine elders"

is to secure the help of the spirit world, including the Great

Spirit (Wakan Tanka in the language of the Lakota

Sioux), for the

benefit of the entire community.Sometimes the help sought may be for the sake of healing disease, sometimes it may be for the sake of healing the psyche, sometimes the goal is to promote harmony between human groups or between humans & nature. So the term "medicine man/woman" is not entirely inappropriate, but it greatly oversimplifies and also skews the depiction of the people whose role in society complements that of the chief. These people are not the Native American equivalent of the Chinese "barefoot doctors", herbalists, nor of the emergency medical technicians who ride rescue vehicles.

To be recognized as the one who performs this function of bridging between the natural world and the spiritual world for the benefit of the community, an individual must be validated in his role by that community. Medicine men and women study through a medicine society or from a single teacher.

Cultural context:

Cultural context:

An Ojibwa Midew

("medicine man") preparing an herbal remedy.

The term "medicine people" is commonly used in

Native American communities, for example, when Arwen Nuttall (Cherokee) of

the National Museum of the American

Indian writes, "The knowledge possessed by medicine people is

privileged, and it often remains in particular families."Native Americans tend to be quite reluctant to discuss issues about medicine or medicine people with non-Indians.

In some cultures, the people will not even discuss these matters with Indians from other tribes. In most tribes medicine elders are not expected to advertise or introduce themselves as such. As Nuttall writes, "An inquiry to a Native person about religious beliefs or ceremonies is often viewed with suspicion.

One example of this was the Apache medicine cord or Izze-kloth, whose purpose and use by Apache medicine elders was a mystery to nineteenth century ethnologists because "the Apache look upon these cords as so sacred that strangers are not allowed to see them, much less handle them or talk about them."

The 1954 version of Webster's New World Dictionary of

the American Language, reflects the poorly grounded perceptions of the

people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that

time: "a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and

controlling spirits." In effect, such definitions were not explanations of

what these "medicine people" were to their own communities, but

instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote

observers when they tried to categorize these individuals.

The 1954 version of Webster's New World Dictionary of

the American Language, reflects the poorly grounded perceptions of the

people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that

time: "a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and

controlling spirits." In effect, such definitions were not explanations of

what these "medicine people" were to their own communities, but

instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote

observers when they tried to categorize these individuals.The term "medicine man/woman" like the term "shaman", has been criticized by Native Americans, as well as other specialists in the fields of religion and anthropology.

The term "medicine man/woman" was also frequently used by Europeans to refer to African traditional healers, also known as "witch doctors" or "fetish men/women".

RITUAL MASKS

Ritual masks occur throughout the world, and although they

tend to share many characteristics, highly distinctive forms have developed.

Ritual masks occur throughout the world, and although they

tend to share many characteristics, highly distinctive forms have developed. The function of the masks may be magical or religious; they may appear in rites of passage or as a make-up for a form of theatre.

Equally masks may disguise a penitent or preside over important ceremonies; they may help mediate with spirits, or offer a protective role to the society who utilise their powers.

Biologist Jeremy Griffith has suggested that ritual masks, as representations of the human face, are extremely revealing of the two fundamental aspects of the human psychological condition: firstly, the repression of a cooperative, instinctive self or soul; and secondly, the extremely angry state of the unjustly condemned conscious thinking egocentric intellect.

North

America:

North

America:

Arctic Coastal groups have tended towards

rudimentary religious practice but a highly evolved and rich mythology,

especially concerning hunting.

In some areas annual shamanic ceremonies involved masked dances and these strongly abstracted masks are arguably the most striking artifacts produced in this region.

In some areas annual shamanic ceremonies involved masked dances and these strongly abstracted masks are arguably the most striking artifacts produced in this region.

Inuit groups vary widely and do not

share a common mythology or language.

Not surprisingly their mask traditions are also often different, although their masks are often made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones and feathers.

Not surprisingly their mask traditions are also often different, although their masks are often made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones and feathers.

Pacific Northwest Coastal indigenous groups were generally highly skilled woodworkers.

Their masks were often master-pieces of carving, sometimes with movable jaws, or a mask within a mask, and parts moved by pulling cords.

The carving of masks was an important feature of wood craft, along with many other features that often combined the utilitarian with the symbolic, such as shields, canoes, poles and houses

.

Their masks were often master-pieces of carving, sometimes with movable jaws, or a mask within a mask, and parts moved by pulling cords.

The carving of masks was an important feature of wood craft, along with many other features that often combined the utilitarian with the symbolic, such as shields, canoes, poles and houses

.

Woodland tribes, especially in the

North-East and around the Great Lakes, cross-fertilized culturally with one another.

The Iroquois made spectacular wooden ‘false face’ masks, used in healing ceremonies and carved from living trees.

These masks appear in a great variety of shapes, depending on their precise function.

The Iroquois made spectacular wooden ‘false face’ masks, used in healing ceremonies and carved from living trees.

These masks appear in a great variety of shapes, depending on their precise function.

Pueblo craftsmen produced impressive work

for masked religious ritual, especially the Hopi and Zuni.

Pueblo craftsmen produced impressive work

for masked religious ritual, especially the Hopi and Zuni. The kachinas, god/spirits, frequently take the form of highly distinctive and elaborate masks that are used in ritual dances.

These are usually made of leather with appendages of fur, feathers or leaves.

Some cover the face, some the whole head and are often highly abstracted forms.

Navajo masks appear to be inspired by the Pueblo prototypes.

In more recent times, masking is a

common feature of Mardi Gras traditions, most notably in New Orleans. Costumes and masks (originally

inspired by masquerade balls) are frequently worn by krewe members on Mardi Gras Day.

Laws against concealing one's identity with a mask are suspended for the day.

Laws against concealing one's identity with a mask are suspended for the day.

FETISHISM

Since prehistoric times, Native

American sculptures have been very popular.

Since prehistoric times, Native

American sculptures have been very popular. Archeologists have found many carvings such as fetishes. Fetishes are the Native American sculptures or carvings of animals that are often used in religious ceremonies.

The

Native Americans believe that these fetishes have supernatural energies.

Many times today, especially the Zuni still carve fetishes.

This beautiful art form may be decorated with stones, shells, and feathers.

Many times today, especially the Zuni still carve fetishes.

This beautiful art form may be decorated with stones, shells, and feathers.

The earliest form of Native American

sculptures such as fetishes were what the Zuni tribe called Ahlashiwe.

The Zuni believe that these sculptures were real animals that had been turned to stone by the sons of the Sun Father.

This meant their life force was still inside the stone and these fetishes were treated as very powerful.

The Zuni believe that these sculptures were real animals that had been turned to stone by the sons of the Sun Father.

This meant their life force was still inside the stone and these fetishes were treated as very powerful.

Fetishes were also seen as powerful because they connected us to our planet and

the Native Americans believed that everything had an invisible spirit and

therefore held powers.

The animal sculptures were believed

to have contained the spirit of the animal it represented.

The Zuni believe there were six animals that represented the six directions.

The Zuni believe there were six animals that represented the six directions.

The mountain

lion represents the north.

This fetish can be used to protect people going on long journey or working on long term projects.

This fetish can be used to protect people going on long journey or working on long term projects.

The wolf

represents the east.

This fetish helps one when searching for game, but also when searching for answers to their destiny.

This fetish helps one when searching for game, but also when searching for answers to their destiny.

The badger represents

the south.

This fetish helps people find the correct herbs for healing ailments.

The bear represents the west.

This fetish too involves healing, but not only the body, but also the spirit.

This fetish helps people find the correct herbs for healing ailments.

The bear represents the west.

This fetish too involves healing, but not only the body, but also the spirit.

The mole represents

the earth.

This fetish can be used to protect crops.

This fetish can be used to protect crops.

The eagle

represents the sky.

This fetish also involved healing, but it can take one into the spirit world where they can seek answers to questions about healing.

This fetish also involved healing, but it can take one into the spirit world where they can seek answers to questions about healing.

Some Native American sculptures will

have a coral heart line on both sides. This heart line usually runs from

the mouth or nose to where the heart lies.

Some Native American sculptures will

have a coral heart line on both sides. This heart line usually runs from

the mouth or nose to where the heart lies. An arrowhead may symbolize the heart line or life force.

Some fetishes may also come with decorations such as turquoise, coral, an arrowhead, or feathers. These are considered offerings to evoke the spirit of the fetish.

The Native Americans view the

fetishes as many view saints or a sacred statue. It can be used when you

need to pray or meditate.

The animal fetish also reminds us that we all need aid with challenges from time to time. In addition, we realize that all things live are interconnected with each other.

The animal fetish also reminds us that we all need aid with challenges from time to time. In addition, we realize that all things live are interconnected with each other.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)